Third Text

- Abigail Reynolds: Walking A Cappella

- On the Necessity of Art Against Censorship and Resignation: ‘we refuse_d’ at Mathaf in Doha (31 October 2025 – 9 February 2026)

- An Interview with Osei Bonsu

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘UnMyth: Works and Worlds of Mithu Sen’

- ‘MONUMENTS’ at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and The Brick, Los Angeles

- ‘The Land Sings Back’ at Drawing Room, London

- ‘Les Rencontres d’Arles 2025’ meets with the Global South

- ‘All Directions’, the Fenix Museum, Rotterdam

- With a disco ball in hand: 12 hours to dismantle the master’s house – The Ignorant Art School’s Sit-in #4: 12 Hour Acting Up

- Strangers Everywhere or Apocalypse is Always Now: Notes from the 60th Venice Biennial

- Michelle Williams Gamaker: Live in Analysis – ‘Strange Evidence’ with Anouchka Grose at Matt’s Gallery, London, 4 July 2025

- An Interview with Ibrahim Mahama

- Ioana Leca, Artistic Director of the Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (GIBCA), in conversation with Jelena Sofronijevic

- ‘Only Your Name’: On Loss and Longing for Vietnam

- ‘Electric Dreams: Art and Technology before the Internet’, Tate Modern, London, 28 November 2024 – 1 June 2025

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘How Secular is Art? On the Politics of Art, History, and Religion in South Asia’, edited by Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Vazira Zamindar

- Building or Undoing Worlds? ‘Janiva Ellis: Fear Corroded Ape’ at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, 31 January – 6 April 2025

- ‘Ruth Asawa: Retrospective’ at San Francisco’s MOMA, 5 April – 2 September 2025

- ‘Sharjah Biennial 16: to carry’

- ‘uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things’: The Liverpool Biennial, 10 June – 17 September 2023

- Iron Souths? – A report on the ‘Iron Curtains or Artistic Gates? Communism and Cultural Diplomacy in the Global South’ workshop in Vienna, September 2024

- ‘The Only Door I Can Open: Women Exposing Prison Through Art’ at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco

- ‘All We Imagine as Light’ as Existentialist Feminist Art

- ‘Nurture Gaia’: The Bangkok Art Biennale 2024

- ‘Noah Davis’ at the Barbican, London

- Long-Distance Friendships: Exploring Black Narratives in Eastern European Art Exhibitions

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Trevor Paglen: Adversarially Evolved Hallucinations’, edited by Anthony Downey (Research/Practice 04, Sternberg Press, 2024)

- The Angel of History at the Threshold – A Future Placed in the Past: Yael Bartana and Ersan Mondtag in ‘Thresholds’ in the German pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale

- ‘Pauline Curnier Jardin’ at Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Helsinki, 11 October 2024 – 23 February 2025

- Ariella Aïsha Azoulay on ‘The Jewelers of the Ummah: A Potential History of the Jewish Muslim World’

- In-betweens: Mónica Alcázar-Duarte at Autograph

- An Interview with Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum

- An Interview with Kenturah Davis

- ‘Revolutionary Romances? Globale Kunstgeschichten in der DDR’ (Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR) at the Albertinum, Dresden

- On the nature of using and reusing: An interview with Eliza Kentridge

- ‘Josh Kline: Climate Change’ at MOCA, Los Angeles

- Dismantling the Monuments: Artistic approaches in the making of ‘Luka dan Bisa Kubawa Berlari’

- Mischief and Mimicry: Phyllida Barlow

- An interview with Otobong Nkanga

- After Gaza, Reflecting on ‘Auschwitz: Not long ago. Not far away’ in Boston

- ‘Tavares Strachan: There Is Light Somewhere’ at London’s Hayward Gallery

- ‘Don’t Kiss and Tell’: The work of Maria Madeira in the Timor-Leste pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale

- What do we want from our entangled pasts? ‘Entangled Pasts, 1768–now: Art, Colonialism and Change’ at London’s Royal Academy

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Mary Kelly’s Concentric Pedagogy: Selected Writings’, edited by Juli Carson (Bloomsbury, 2024)

- The Weirdness and Materialism of ‘Al Fitna Al Kubra’: ‘Muawiya’s Thread’ at 32Bis, Tunis

- BOOK REVIEW: Arnd Schneider, ‘Expanded Visions: A New Anthropology of the Moving Image’ (Routledge, 2021)

- ‘Sonya Clark: We Are Each Other’

- Interspecies Solidarities at the Carnival of Extinctions: The Non-Human Foreigner at the 60th Venice Biennial

- BOOK REVIEW: Noam Shoked, ‘In the Land of the Patriarchs: Design and Contestation in West Bank Settlements’ (University of Texas Press, 2023)

- A Resistant Gaze? ‘RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology’ at London’s Barbican Art Gallery

- ‘A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography’ at Tate Modern

- Pedagogies of Transmission in ‘ ...But There Are New Suns’: The Ignorant Art School Sit-in #3 with The Otolith Group

- BOOK REVIEW: Janette Parris, ‘This Is Not A Memoir’ (Montez Press, 2023)

- ‘Pacita Abad’ at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 21 October 2023 – 28 January 2024

- ‘Revolutionary Romances: Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR – Prologue’ at the Albertinum, Dresden, 2022

- ‘Against Apartheid’ at KARST Contemporary Arts, Plymouth, 29 September – 2 December 2023

- BOOK REVIEW: Myron M Beasley, ‘Performance, Art, and Politics in the African Diaspora: Necropolitics and the Black Body’

- 40th EVA International: Ireland’s Biennial of Contemporary Art

- BOOK REVIEW: 'Shona Illingworth: Topologies of Air', edited by Anthony Downey (Sternberg Press and The Power Plant, 2022)

- Claiming Spaces for Justice: Art, Resistance and Finding One Another in Bogotá

- Life Is More Important Than Art

- Taking Visual Pleasure in Taking Cinematic Revenge: Michelle Williams Gamaker’s ‘Our Mountains are Painted On Glass’

- Richard Mosse’s 'Broken Spectre' (2018–2022)

- What happens if a contemporary artist places a jewellery shop inside a gallery? R.I.P. Germain: “Jesus Died For Us, We Will Die For Dudus!” at the ICA

- Life is the Institution: A Contingent View on Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Macedonian Art

- Hangama Amiri’s ‘A Homage to Home’ at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, and in the Sharjah Biennial

- BOOK REVIEW: Nicholas Gamso, 'Art after Liberalism', 2021

- ‘Harun Farocki: Consider Labour’, at Cooper Gallery, University of Dundee, 3 February – 1 April 2023

- Lana Locke’s ‘Relic Garden’ at Lungley Gallery, London, UK, 3 March – 15 April 2023

- Report on the Baltics: Three Exhibitions in Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Art and Solidarity Reader: Radical Actions, Politics and Friendships’

- ‘Soft and Weak Like Water’: The 14th Gwangju Biennale, 2023

- A Personal Response to Steve McQueen’s 'Grenfell'

- ‘2022 Title Match: IM Heung-soon vs Omer Fast “Cut!”’ at SeMA in Seoul

- United Colours of the UAAC: More on the Politics of Diversity in Canada

- Life is Art: An Interview with Leonhard Frank Duch

- Performing History: Jelili Atiku’s performances, Lubaina Himid’s and Kimathi Donkor’s 'Toussaint Louverture', Steve McQueen’s 'Carib’s Leap' and Yinka Shonibare’s 'Mr and Mrs Andrews'

- BOOK REVIEW: Serge Daney, ‘The Cinema House & the World: The Cahiers du Cinema Years 1962–1981’

- ‘We can’t be provincial about Venice’: An interview with Jane da Mosto

- ‘52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

- ‘Into View: Bernice Bing’ at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

- Through the Algorithm: Empire, Power and World-Making in Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s ‘If only this mountain between us could be ground to dust’ at the Art Institute Chicago

- Intimate Estrangements: ‘Bharti Kher: The Body is a Place’ at the Arnolfini

- BOOK REVIEW: Jacob Lund, ‘The Changing Constitution of the Present: Essays on the Work of Art in Times of Contemporaneity’

- Lumbung will Continue (Somewhere Else): Documenta Fifteen and the Fault Lines of Context and Translation

- British Art Show 9

- On and Off ‘Ĩ NDAFFA #’: An Extended Review of the 14th Dakar Biennale

- Behind the Algorithm: Migration, Mexican Women and Digital Bias – Mónica Alcázar-Duarte’s ‘Second Nature’

- BOOK REVIEW: Banu Karaca, ‘The National Frame: Art and State Violence in Turkey and Germany’

- Fiona Tan: ‘With the Other Hand’

- Notes on the Palestine Poster Project Archive: Ecological Imaginaries, Iconographies, Nationalisms and Knowledge in Palestine and Israel, 1947–now

- Diversity and Decoloniality: The Canadian Art Establishment’s New Clothes

- Cathy Lu’s ‘Interior Garden’ at the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco

- ‘In the Black Fantastic’: Afro-futurism Arrives at the Hayward Gallery

- On Caring Institutions, Safe Spaces and Collaborations beyond Exhibitions: An Interview with Robert Gabris

- Media Aesthetics of Collaborative Witnessing: Three Takes on ‘Three Doors – Forensic Architecture / Forensis, Initiative 19. Februar Hanau, Initiative in Gedenken an Oury Jalloh’ at Frankfurter Kunstverein

- Obituary: Marisa Rueda, 1941–2022

- The End Begins: A dialogue between Renan Porto and Julia Sauma, on the dialogue between Antonio Tarsis and Anderson Borba in ‘The End Begins at the Leaf’

- Sonia Boyce: Feeling Her Way at the Venice Biennale

- Clarissa Tossin: ‘Falling From Earth’

- The Collective Model: documenta fifteen

- Programmed Visions and Techno-Fossils: Heba Y Amin and Anthony Downey in conversation

- Reflections on Coleman Collins’s ‘Body Errata’ at Brief Histories, New York: Coleman Collins in conversation with Erik DeLuca

- Southern Atlas: Art Criticism in/out of Chile and Australia during the Pinochet Regime

- Jimmie Durham, ‘ “...very much like the Wild Irish”: Notes on a Process which has no end in sight’

- Jimmie Durham, ‘Those Dead Guys for a Hundred Years’

- The Many Faces of the Artist’s Studio – ‘A Century of the Artist’s Studio: 1920−2020’ at London’s Whitechapel Gallery

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Critical Zones – The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth’, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Wiebel

- Jimmie Durham, ‘A Certain Lack of Coherence’

- ‘Thought is Made in The Mouth’: Radical nonsense in pop, art, philosophy and art criticism

- Empowering Bare Lives: ‘Bordered Lives’ at the Austrian Association of Women Artists (VBKÖ), Vienna

- The Moral Stake of Gamification – On the ‘Black Swan: The Communes’ hackathon at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, August 2021

- ‘Departures’ at the Migration Museum, London

- BOOK REVIEW: David Elliott, ‘Art & Trousers: Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Asian Art’

- Jumping Out of the Trick Bag: Frank Bowling’s Lands of Many Waters at the Arnolfini

- Drawing From and With the Oceanic: Tania Kovats at Parafin, London

- BOOK REVIEW: Rachel Zolf, ‘No One’s Witness: A Monstrous Poetics’

- ‘Judy Baca: Memorias de Nuestra Tierra, a Retrospective’ at the Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California

- ‘Remembering in Art’: Kristina Chan in Conversation

- Living through Archives: The socio-historical memories, multimedia methodologies and collaborative practice of Rita Keegan

- Decolonising Dance Movement Therapy: A Healing Practice Stuck between Coloniality and Nationalism in Sri Lanka

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Feminism and Art in Postwar Italy: The Legacy of Carla Lonzi’, edited by Francesco Ventrella and Giovanna Zapperi

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Don’t Follow the Wind’, edited by Nikolaus Hirsch and Jason Waite

- Moyra Davey’s ‘Index Cards’ (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020) and ‘I Confess’ (Dancing Foxes, Press 2020)

- Why do we need Aby Warburg today? Or, is image memory a bodily sensation?

- BOOK REVIEW: Susan Schuppli, ‘Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence’

- Reflections on the Future and Past of Decolonisation: Africa and Latin America

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Under the Skin: Feminist Art and Art Histories from the Middle East and North Africa Today’

- Weaving and Resistance in Hana Miletić’s ‘Patterns of Thrift’

- BOOK REVIEW: Alana Hunt, ‘Cups of nun chai’

- BOOK REVIEW: The Avant-Garde Museum

- BOOK REVIEW: Dan Hicks, ‘The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution’

- Manora Field Notes & Beyond: A conversation with Naiza Khan

- Cara Despain, ‘From Dust’: Viewing the American West through a Cold War Lens

- ‘MONOCULTURE: A Recent History’ at M HKA

- Yishay Garbasz, in conversation with Sarah Messerschmidt

- ‘Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI’

- An Aesthetics of Prolepsis

- ‘Piercing Brightness’, by Shezad Dawood: Migration, Memory and Multiculturalism

- BOOK REVIEW: Deserting from the Culture Wars

- BOOK REVIEW: Saloni Mathur, ‘A Fragile Inheritance: Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian Art’

- At their word: Forensic Architecture’s renouncement and re-announcement of police testimonies in the investigation into the killing of Mark Duggan

- BOOK REVIEW: Sam Bardaouil, ‘Surrealism in Egypt: Modernism and the Art and Liberty Group’

- A conversation with Mohamed Melehi

- Heritage is to Art as the Medium is to the Message: The Responsibility to Palestinian Tatreez

- ‘We’, A Global Community Suspended in Time and Space: A Study of İnci Eviner’s Work in the 2019 Venice Biennial

- Grab the Form: A Conversation with Hafiz Rancajale

- ‘A Matter of Liberation: Artwork from Prison Renaissance’

- The Colonial Spectre of Classicism: Reflections on ‘White Psyche’ at The Whitworth Gallery

- BOOK REVIEW: Engagement or Acquiescence? On ‘Critique in Practice: Renzo Martens’ Episode III: Enjoy Poverty’

- ‘Errata’ in retro-prospect

- Cameron Rowland, ‘3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73’

- Pushing against the roof of the world: ruangrupa’s prospects for documenta fifteen

- BOOK REVIEW: Tom Holert, ‘Knowledge Beside Itself: Contemporary Art’s Epistemic Politics’

- BOOK REVIEW: Laleh Khalili, ‘Sinews of War and Trade: Shipping and Capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula’

- Maria Thereza Alves’s ‘Recipes for Survival’

- To Don Duration: Lisl Ponger’s ‘The Master Narrative und Don Durito in 10 Chapters’

- BOOK REVIEW: Oliver Marchart, ‘Conflictual Aesthetics’

- Karol Radziszewski's ‘The Power of Secrets’

- The Method of Abjection in Mati Diop’s ‘Atlantics’

- How are the visual arts responding to the COVID-19 crisis?

- Art in Contemporary Afghanistan

- BOOK REVIEW: Kate Morris, ‘Shifting Grounds: Landscape in Contemporary Native American Art’

- Boring, Everyday Life in War Zones: A conversation with Jonathan Watkins

- ‘Luchita Hurtado: I Live I Die I Will be Reborn’

- Movements, Borders, Repression, Art: An interview with artist Zeyno Pekünlü, March 2020

- ‘Shoplifting from Woolworths and Other Acts of Material Disobedience’, an exhibition of work by Paula Chambers

- Images in Spite of All: ZouZou Group's film installation ‘– door open –’

- Kamal Boullata: For the Love of Jerusalem

- Paul O'Kane, ‘The Carnival of Popularity Part II: Towards a “mask-ocracy”’

- BOOK REVIEW: Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, ‘Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism’

- ‘Knotworm’: Pauline de Souza interviews Sam Keogh

- BOOK REVIEW: Vessela Nozharova, ‘Introduction to Bulgarian Contemporary Art 1982–2015’

- A Place for/in Place of Identity? A conversation with Larissa Sansour

- Danh Vo’s Exorcism of Vietnam

- BOOK REVIEW: Jessica L Horton, ‘Art for an Undivided Earth: The American Indian Movement Generation’

- In conversation with Adam Pendleton: What is Black Dada?

- Edward Chell: ‘Common Ground’

- BOOK REVIEW: Jonas Staal, ‘Propaganda Art in the 21st Century’

- The 2019 Istanbul Biennial

- The Aliveness of Moses Quiquine

- ‘Terror Nullius’ by Soda_Jerk

- Archive Matters: Fiona Tan at the Ludwig Museum

- Communicating Difficult Pasts: A Latvian initiative explores artistic research on historical trauma

- BOOK REVIEW: Translating the World into Being - A review of ‘At Home in the World: The Art and Life of Gulammohammed Sheikh’

- Visiting the Arabian Peninsula: A Brief Glimpse of Contemporary and Not-So-Contemporary Art and Culture in KSA, aka the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- [AR]T, Apple and Us

- BOOK REVIEW: David Burrows and Simon O’Sullivan, ‘Fictioning: The Myth-Functions of Contemporary Art and Philosophy’

- Art and Theory in an Anti-fascist Year: An Interview with Kuba Szreder

- Paul O’Kane, ‘The Carnival of Popularity’

- BOOK REVIEW: Nora Sternfeld, ‘Das radikaldemokratische Museum’

- The 2019 Whitney Biennial

- ‘Passage to Asylum: The Journey of a Million Refugees’ – Dilpreet Bhullar in conversation with Kalyani Nedungadi and Maya Gupta

- On Brexit in Vienna: Mirroring the Social Decay

- Forever Young: Juvenilia, Amateurism, and the Popular Past (or ‘Transvaluing Values in the Age of the Archive’)

- Captain Cook Reimagined from the British Museum’s Point of View

- Okwui Enwezor: In Memoriam

- BOOK REVIEW: Chad Elias, ‘Posthumous Images: Contemporary Art and Memory Politics in Post-Civil War Lebanon’

- Arthur Jafa at the Berkeley Art Museum

- Repair, Ergonomics & Quantum Physics: Reflections on how Cairo’s contemporary art scene is reviving vanishing futures

- Vivan Sundaram: Disjunctures

- Rome Leads to All Roads: Power, Affection and Modernity in Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Roma’

- Still Caught in the Acts: ‘Mating Birds Vol. 2’

- A Political Gemstone Kingdom of Natural–Cultural Feelings from Bucharest to Warsaw: Larisa Crunțeanu’s ‘Aria Mineralia’ exhibition

- INTERVIEW: The Politics of Shame – Ai Weiwei in conversation with Anthony Downey

- BOOK REVIEW: Renate Dohmen’s ‘Encounters Beyond the Gallery’

- Juliet Steyn reviews Juan Cruz’s ‘I don’t know what I’m doing but I’m trying very hard.’

- INTERVIEW: Mediating Social Media – Akram Zaatari in Conversation with Anthony Downey

- An Indigenous Intervention: Richard Bell’s Salon des Refusés at the 2019 Venice Biennale

- INTERVIEW: Sunil Shah, ‘Uganda Stories’

- Zarina’s ‘Dark Roads’: Exile, Statelessness and the Tenacity of Nostalgia

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Fahrelnissa Zeid: Painter of Inner Worlds’ by Adila Laïdi-Hanieh

- BOOK REVIEW: Iain Chambers, ‘Postcolonial Interruptions, Unauthorised Modernities’

- The 2017 Venice Biennale and the Colonial Other

- BOOK REVIEW: David Kunzle, ‘CHESUCRISTO: The Fusion in Image and Word of Che Guevara and Jesus Christ’

- Longing for Heterotopia: ‘Silver Sehnsucht’ in Silvertown

- BOOK REVIEW: Future Imperfect: Contemporary Art Practices and Cultural Institutions in the Middle East

- Art as Anachronism

- INTERVIEW: John Akomfrah

- Steven Eastwood: ‘the interval and the instant’

- BOOK REVIEW: Open Systems Reader - Tomorrow is not Promised! edited by Gulsen Bal

- Paul O’Kane, ‘The Other Side of the Word: Translation as Migration in the Anthologised Writings of Lee Yil’

- ‘The Self-Evolving City’: Architecture and Urbanisation in Seoul

- The Folkestone Triennial 2017

- Sharjah Biennial 13 Offsite: Ramallah

- Theory of the Unfinished Building: On the Politico-Aesthetics of Construction in China

- Marcus Verhagen, ‘Flows and Counterflows: Globalisation in Contemporary Art’

- An Architecture of Memory

- Learning from documenta 14: Athens, Post-Democracy, and Decolonisation

- BOOK REVIEW: Joan Key, ‘Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method’

- Kader Attia: Dispossession

- BOOK REVIEW: Zhuang Wubin, ‘Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey’

- Spectral Anxieties of Postculture

- 'Exercises of Freedom': Documenta 14

- Bloom

- Artes Mundi 7

- Post-Perspectival Art and Politics in Post-Brexit Britain: (Towards a Holistic Relativism)

- A Short History of Blasphemy

- BOOK REVIEW: Moulim El Aroussi, ‘Visual Arts in the Kingdom of Morocco’

- The Vicissitudes of Conduct

- South Korea’s Painful Past

- Return of the Condor Heroes and Other Narratives

- ‘The Savage Hits Back’ Revisited: Art and Global Contemporaneity in the Colonial Encounter

- The Unrepresentables

- From a Postconceptual to an Aporetic Conception of the Contemporary

- Christof Mascher: Memory Palace

- The 6th Marrakech Biennale, 2016: ‘Not New Now’

- The 2015 Venice Biennale

- Art in the Time of Colony

- Brad Prager, After the Fact: The Holocaust in Twenty-First Century Documentary Film

- In Media Res: Heiner Goebbels, Aesthetics of Absence: Text on Theatre

- Failure as Art and Art History as Failure

- Restrictions Apply

- 13th Istanbul Biennial

- ‘Re: turn’: Bashir Makhoul

- Global Occupations of Art

- The Politics of Identity for Korean Women Artists Living in Britain

- Art Beyond Conflict

- David Craven’s Future Perfect

- Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology

A Short History of Blasphemy

"Whether ‘imaging badly’ in speech, or ‘speaking evil’ in images, blasphemy has long been with us. But as far as I know, the Greek word blasphemy (βλασφημέω) does not appear in Homer or Hesiod. Liddell and Scott have it first in Euripides’ Ion and then in Plato’s Laws (‘when some worshipper… breaks down into downright blasphemy’). Blasphemy seems to have come in with philosophy and law, especially when the Law, ‘that which is laid down’, became explicit enough to distinguish between ‘evil speaking’ (blasphemy) and its opposite, ‘virtuous speaking’ (euphemism), in a legal sense. Blame is a doublet of blasphemy, and the law is concerned with assigning and apportioning blame; or fame, which is also based on what is said about someone or something."

David Levi Strauss

‘Red for the judges and black for the priests’

- Jean Genet on Stendhal, to Mohamed Choukri, in Jean Genet in Tangier (1974)

In Book II of the Republic, Socrates discusses with Adimantus and Glaucon the origins of justice and injustice in states, and at a certain point it becomes clear that blasphemy is key to these origins. Socrates is presenting his brief against the ‘false stories’ of the poets Homer and Hesiod, contending that these stories corrupt the youth. The blame comes, he says, ‘When anyone images badly in his speech the true nature of gods and heroes, like a painter whose portraits bear no resemblance to his models’ (377, e, my emphasis). This lack of verisimilitude is not only aesthetically displeasing; it is injurious to the state. This is in the middle of Plato’s most full-throated censure of the poets and their blasphemies, in which he claims, ‘while they speak evil of the gods they at the same time make cowards of the children’ (381, e). Homer and Hesiod are singled out because ‘there is no lying poet in God’ (382, d). As it turned out, of course, there is no lying philosopher in God, either, and Socrates was eventually tried for blasphemy (against the Athenian ideal of the polis, really), found guilty, and suffered the ultimate punishment.

But since blasphemy breaches the unspeakable, it is clearly in the realm of the poets. Poets are makers (poein); they make things up. When I was a young poet in San Francisco, Eric Havelock’s Preface to Plato was an important book among the poets who were my teachers in the Poetics Program at New College. Robert Duncan had gotten the book from Charles Olson, who called it ‘the only work in criticism which is relevant at all to developments in thought and poetry over the past 150 years’. Havelock’s thesis is that Plato’s condemnation of the poets in the Republic is based on the fact that the oral tradition of Homer and Hesiod had become a technological obstacle to the new ways of thinking being brought about through literacy. I teach Preface to Plato now, partly because Havelock’s well-formed argument about the transition from the technologies of orality to literacy is useful today as an analogy for our current transition from literacy to the image.

Whether ‘imaging badly’ in speech, or ‘speaking evil’ in images, blasphemy has long been with us. But as far as I know, the Greek word blasphemy (βλασφημέω) does not appear in Homer or Hesiod. Liddell and Scott have it first in Euripides’ Ion and then in Plato’s Laws (‘when some worshipper… breaks down into downright blasphemy’). Blasphemy seems to have come in with philosophy and law, especially when the Law, ‘that which is laid down’, became explicit enough to distinguish between ‘evil speaking’ (blasphemy) and its opposite, ‘virtuous speaking’ (euphemism), in a legal sense. Blame is a doublet of blasphemy, and the law is concerned with assigning and apportioning blame; or fame, which is also based on what is said about someone or something.

The Law, expressing the divine will of God, was laid down in the Pentateuch. It is often asserted that the Mosaic law against blasphemy is revealed in Leviticus 24:16, but the truth is that the law is already a given there, and this passage is a legal clarification of its reach. Shelomith’s son comes into the camp and curses the name of the Lord. The problem is that Shelomith is an ‘Israelitish’ woman (in the King James Version), meaning she is only half-Israelite. So the question is, does the law against blasphemy apply to this mixed-blood offspring? The people bring him to Moses because they’re not sure whether the law applies equally to a half- or quarter-Israelite. Jehovah speaks to Moses and says that everyone who heard the blasphemer should lay their hands on his head and stone him to death. The stranger is, in effect, judged to be worthy of punishment.

In the Gospels, Jesus loosens the penalties against blasphemy somewhat, but there are still fine points of law to attend to. In Matthew 12:22–31 and Mark 3:22–30, an exception to the New Testament leniency in response to blasphemy is identified: blasphemy against the Holy Ghost. This particular offense is distinctly unforgiveable, leading to eternal damnation. Why? Because he who would blaspheme against the Holy Ghost has ‘an unclean spirit’. He is also, presumably, an adversary of Jesus, a Pharisee, who attributed Christ’s miracles not to the Holy Ghost, but to the workings of Beelzebub. That is what is unforgiveable. Blame and fame are not appropriately apportioned.

Blind singer Marlana VanHoose from Kentucky sings the national anthem at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio, July 18, 2016. Photo by David Levi Strauss.

Blame and fame, in the form of celebrity gossip and scandal, have become ubiquitous in our current image sphere, but the poet and film-maker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s life (1922–1975), death, and work marked a turning point in the modern blasphemy/blame/fame nexus. When his younger brother Guido, a Partisan in the Italian Resistance fighting the Nazis and Fascists, was killed by Yugoslav Communists in a power struggle in 1945, Pasolini was devastated, but still spoke out in favor of Communism as the only way to provide a new culture. Soon after joining the Italian Communist Party, however, he was charged with the corruption of minors and obscene acts and expelled. He fled with his mother to Rome.

On 1 March 1963, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film La ricotta – following a crew making a film about the Passion of Christ, with Orson Welles as the brilliant and loquacious Marxist director – was seized and Pasolini was charged with ‘insulting the religion of the state’. The statute invoked was a remnant of the Rocco Code, the Fascist penal code put in place by Arturo Rocco in 1931. Pasolini was found guilty and sentenced to four months in prison. This sentence was eventually overturned on appeal, but it took three years, during which Pasolini was continually under threat.

The Catholic Church was initially ready to convict him of blasphemy for daring to make a film of The Gospel According to St. Matthew, but this turned out to be one of the most faithful depictions of the Gospels ever put on film. An homage to Pope John XXIII, it found enthusiastic approval when it was shown at the Second Vatican Council. Pasolini considered asking Jack Kerouac to play the role of Christ, but settled on a young Spaniard named Enrique Irazoqui. A twenty-two-year-old Giorgio Agamben also appeared in the film, as Philip the Apostle.

Our current communications environment is preoccupied with arguments about blame and fame. A controversy has erupted over Jann Wenner’s decision to put a dreamy photograph of the Boston Marathon bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev on the cover of the 1 August 2013 issue of Rolling Stone magazine: terrorist as rock star. The result of the controversy was that the issue sold twice as many copies as usual, and the all but extinguished reputation of Rolling Stone for social relevance was briefly revived.

The truth is that blasphemy is still very much with us. Six American states – Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Oklahoma, Michigan, and Wyoming – have laws against blasphemy on the books, as do more than thirty countries. Ireland passed a law against blasphemy in 2009. Huge crowds demonstrated recently in Bangladesh demanding stricter laws against blasphemy. After dancing and shouting ‘Mother Mary please drive Putin away’ for thirty seconds on 21 February 2012 in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, three members of the punk-art collective Pussy Riot were convicted on charges of ‘disrupting social order by an act of hooliganism that showed disrespect for society and is motivated by a religious hatred or enmity’, and two of them, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, are currently serving two-year prison sentences. As the Reverend Chloe Breyer, a priest at Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church in West Harlem, New York, said in response to the Pussy Riot sentences, ‘More often than not, what has been deemed insulting or offensive to God in history has originated in the body or voice of a woman.’

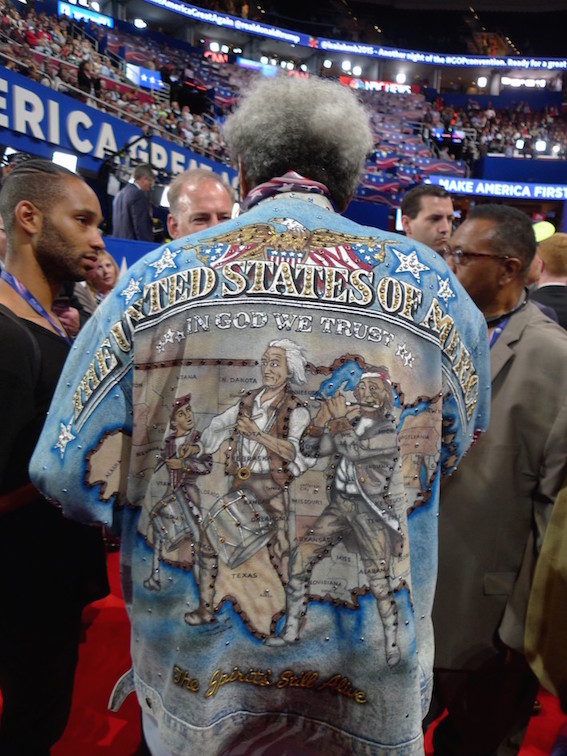

Boxing promoter Don King interviewed at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio, July 18, 2016. Photo by David Levi Strauss.

In his final film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, Pasolini took blasphemy and obscenity back to their source, in language – the language of Sade, yes, but also to the end of language, where power obliterates it. Salò is an unspeakable film.

Pasolini’s blasphemy had previously been directed at the Catholic church as a bourgeois institution, as ‘the merciless heart of the State’.1 But in Salò, he came to the end of the line, to the end of language. Sam Rohdie saw it clearly, in his book The Passion of Pier Paolo Pasolini:

His struggle with the world and himself was essentially aesthetic and linguistic. He wrote not about this or that but purely… To write in such a way is to write parenthetically in order to delay the end of writing and hence keep the ideal alive in ambiguity, in the provisional, as an eternal potential.2

The work of writing that Pasolini left unfinished at his death was titled The Divine Mimesis. It was to be the culmination and new testament of his art, and in it he prophesied his own death, that would prevent him from completing the work, in chilling detail. Pasolini’s friend Giuseppe Zigaina later wrote

It was as if a latter-day saint not recognized by the Catholic church sought martyrdom as a renunciation of mortal life that would at the same time be a passing over to life after death – perhaps to be understood as the artist’s presence in human memory.3

What sets us apart from the gods is death. Gods cannot die, so their narratives have no arc and no end. The human story is finite and thus meaningful. ‘If we were immortal’, wrote Pasolini, ‘we would be immoral, because our example would never have an end; therefore, it would be undecipherable, eternally suspended and ambiguous’.4 In a ‘Note for Canto VII’ of The Divine Mimesis, he wrote,

In this Hell (as in life) cynics are lacking. Nor could I have been one either. I was afraid of it. It seemed dishonorable to me. Perhaps I defended myself from cynicism just because it was a sacred antidote against the ‘wringing of my heart’. I passed, then, like a wind behind the last walls or meadows of the city – or like a barbarian who came down to destroy, and ended by distracting himself by looking, and kissing, someone who resembled himself – before deciding to turn back.5

1 Pier Paolo Pasolini, ‘The Religion of My Time,’ in Poems, Norman MacAfee with Luciano Martinengo, selection and trans, Random House, New York, 1982, p 71

2 Sam Rohdie, The Passion of Pier Paolo Pasolini, British Film Institute and Indiana University Press, London and Bloomington, Indiana, 1995, p 197

3 Bernhart Schwenk and Michael Semff, editors, P.P.P.: Pier Paolo Pasolini and Death, Pinakothek der Moderne and Hatje Cantz, Munich and Ostfildern-Ruit, 2005, p 28

4 Pier Paolo Pasolini, ‘Living Signs and Dead Poets’, in Louise K Barnett, ed, Heretical Empiricism, Ben Lawton and Louise K Barnett, trans, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1988, p 248

5 Pier Paolo Pasolini, The Divine Mimesis, Thomas Erling Peterson, trans, Double Dance Press, Berkeley, California, 1980, p 64

David Levi Strauss is the author of Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow (Aperture, 2014), From Head to Hand: Art and the Manual (Oxford University Press, 2010), Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics, with an introduction by John Berger (Aperture 2003, and in a new edition, 2012), and Between Dog & Wolf: Essays on Art and Politics (Autonomedia 1999, and a new edition, 2010). He is Chair of the graduate program in Art Writing at the School of Visual Arts in New York.