Third Text

- Abigail Reynolds: Walking A Cappella

- On the Necessity of Art Against Censorship and Resignation: ‘we refuse_d’ at Mathaf in Doha (31 October 2025 – 9 February 2026)

- An Interview with Osei Bonsu

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘UnMyth: Works and Worlds of Mithu Sen’

- ‘MONUMENTS’ at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and The Brick, Los Angeles

- ‘The Land Sings Back’ at Drawing Room, London

- ‘Les Rencontres d’Arles 2025’ meets with the Global South

- ‘All Directions’, the Fenix Museum, Rotterdam

- With a disco ball in hand: 12 hours to dismantle the master’s house – The Ignorant Art School’s Sit-in #4: 12 Hour Acting Up

- Strangers Everywhere or Apocalypse is Always Now: Notes from the 60th Venice Biennial

- Michelle Williams Gamaker: Live in Analysis – ‘Strange Evidence’ with Anouchka Grose at Matt’s Gallery, London, 4 July 2025

- An Interview with Ibrahim Mahama

- Ioana Leca, Artistic Director of the Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (GIBCA), in conversation with Jelena Sofronijevic

- ‘Only Your Name’: On Loss and Longing for Vietnam

- ‘Electric Dreams: Art and Technology before the Internet’, Tate Modern, London, 28 November 2024 – 1 June 2025

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘How Secular is Art? On the Politics of Art, History, and Religion in South Asia’, edited by Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Vazira Zamindar

- Building or Undoing Worlds? ‘Janiva Ellis: Fear Corroded Ape’ at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, 31 January – 6 April 2025

- ‘Ruth Asawa: Retrospective’ at San Francisco’s MOMA, 5 April – 2 September 2025

- ‘Sharjah Biennial 16: to carry’

- ‘uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things’: The Liverpool Biennial, 10 June – 17 September 2023

- Iron Souths? – A report on the ‘Iron Curtains or Artistic Gates? Communism and Cultural Diplomacy in the Global South’ workshop in Vienna, September 2024

- ‘The Only Door I Can Open: Women Exposing Prison Through Art’ at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco

- ‘All We Imagine as Light’ as Existentialist Feminist Art

- ‘Nurture Gaia’: The Bangkok Art Biennale 2024

- ‘Noah Davis’ at the Barbican, London

- Long-Distance Friendships: Exploring Black Narratives in Eastern European Art Exhibitions

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Trevor Paglen: Adversarially Evolved Hallucinations’, edited by Anthony Downey (Research/Practice 04, Sternberg Press, 2024)

- The Angel of History at the Threshold – A Future Placed in the Past: Yael Bartana and Ersan Mondtag in ‘Thresholds’ in the German pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale

- ‘Pauline Curnier Jardin’ at Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Helsinki, 11 October 2024 – 23 February 2025

- Ariella Aïsha Azoulay on ‘The Jewelers of the Ummah: A Potential History of the Jewish Muslim World’

- In-betweens: Mónica Alcázar-Duarte at Autograph

- An Interview with Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum

- An Interview with Kenturah Davis

- ‘Revolutionary Romances? Globale Kunstgeschichten in der DDR’ (Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR) at the Albertinum, Dresden

- On the nature of using and reusing: An interview with Eliza Kentridge

- ‘Josh Kline: Climate Change’ at MOCA, Los Angeles

- Dismantling the Monuments: Artistic approaches in the making of ‘Luka dan Bisa Kubawa Berlari’

- Mischief and Mimicry: Phyllida Barlow

- An interview with Otobong Nkanga

- After Gaza, Reflecting on ‘Auschwitz: Not long ago. Not far away’ in Boston

- ‘Tavares Strachan: There Is Light Somewhere’ at London’s Hayward Gallery

- ‘Don’t Kiss and Tell’: The work of Maria Madeira in the Timor-Leste pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale

- What do we want from our entangled pasts? ‘Entangled Pasts, 1768–now: Art, Colonialism and Change’ at London’s Royal Academy

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Mary Kelly’s Concentric Pedagogy: Selected Writings’, edited by Juli Carson (Bloomsbury, 2024)

- The Weirdness and Materialism of ‘Al Fitna Al Kubra’: ‘Muawiya’s Thread’ at 32Bis, Tunis

- BOOK REVIEW: Arnd Schneider, ‘Expanded Visions: A New Anthropology of the Moving Image’ (Routledge, 2021)

- ‘Sonya Clark: We Are Each Other’

- Interspecies Solidarities at the Carnival of Extinctions: The Non-Human Foreigner at the 60th Venice Biennial

- BOOK REVIEW: Noam Shoked, ‘In the Land of the Patriarchs: Design and Contestation in West Bank Settlements’ (University of Texas Press, 2023)

- A Resistant Gaze? ‘RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology’ at London’s Barbican Art Gallery

- ‘A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography’ at Tate Modern

- Pedagogies of Transmission in ‘ ...But There Are New Suns’: The Ignorant Art School Sit-in #3 with The Otolith Group

- BOOK REVIEW: Janette Parris, ‘This Is Not A Memoir’ (Montez Press, 2023)

- ‘Pacita Abad’ at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 21 October 2023 – 28 January 2024

- ‘Revolutionary Romances: Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR – Prologue’ at the Albertinum, Dresden, 2022

- ‘Against Apartheid’ at KARST Contemporary Arts, Plymouth, 29 September – 2 December 2023

- BOOK REVIEW: Myron M Beasley, ‘Performance, Art, and Politics in the African Diaspora: Necropolitics and the Black Body’

- 40th EVA International: Ireland’s Biennial of Contemporary Art

- BOOK REVIEW: 'Shona Illingworth: Topologies of Air', edited by Anthony Downey (Sternberg Press and The Power Plant, 2022)

- Claiming Spaces for Justice: Art, Resistance and Finding One Another in Bogotá

- Life Is More Important Than Art

- Taking Visual Pleasure in Taking Cinematic Revenge: Michelle Williams Gamaker’s ‘Our Mountains are Painted On Glass’

- Richard Mosse’s 'Broken Spectre' (2018–2022)

- What happens if a contemporary artist places a jewellery shop inside a gallery? R.I.P. Germain: “Jesus Died For Us, We Will Die For Dudus!” at the ICA

- Life is the Institution: A Contingent View on Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Macedonian Art

- Hangama Amiri’s ‘A Homage to Home’ at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, and in the Sharjah Biennial

- BOOK REVIEW: Nicholas Gamso, 'Art after Liberalism', 2021

- ‘Harun Farocki: Consider Labour’, at Cooper Gallery, University of Dundee, 3 February – 1 April 2023

- Lana Locke’s ‘Relic Garden’ at Lungley Gallery, London, UK, 3 March – 15 April 2023

- Report on the Baltics: Three Exhibitions in Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Art and Solidarity Reader: Radical Actions, Politics and Friendships’

- ‘Soft and Weak Like Water’: The 14th Gwangju Biennale, 2023

- A Personal Response to Steve McQueen’s 'Grenfell'

- ‘2022 Title Match: IM Heung-soon vs Omer Fast “Cut!”’ at SeMA in Seoul

- United Colours of the UAAC: More on the Politics of Diversity in Canada

- Life is Art: An Interview with Leonhard Frank Duch

- Performing History: Jelili Atiku’s performances, Lubaina Himid’s and Kimathi Donkor’s 'Toussaint Louverture', Steve McQueen’s 'Carib’s Leap' and Yinka Shonibare’s 'Mr and Mrs Andrews'

- BOOK REVIEW: Serge Daney, ‘The Cinema House & the World: The Cahiers du Cinema Years 1962–1981’

- ‘We can’t be provincial about Venice’: An interview with Jane da Mosto

- ‘52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

- ‘Into View: Bernice Bing’ at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

- Through the Algorithm: Empire, Power and World-Making in Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s ‘If only this mountain between us could be ground to dust’ at the Art Institute Chicago

- Intimate Estrangements: ‘Bharti Kher: The Body is a Place’ at the Arnolfini

- BOOK REVIEW: Jacob Lund, ‘The Changing Constitution of the Present: Essays on the Work of Art in Times of Contemporaneity’

- Lumbung will Continue (Somewhere Else): Documenta Fifteen and the Fault Lines of Context and Translation

- British Art Show 9

- On and Off ‘Ĩ NDAFFA #’: An Extended Review of the 14th Dakar Biennale

- Behind the Algorithm: Migration, Mexican Women and Digital Bias – Mónica Alcázar-Duarte’s ‘Second Nature’

- BOOK REVIEW: Banu Karaca, ‘The National Frame: Art and State Violence in Turkey and Germany’

- Fiona Tan: ‘With the Other Hand’

- Notes on the Palestine Poster Project Archive: Ecological Imaginaries, Iconographies, Nationalisms and Knowledge in Palestine and Israel, 1947–now

- Diversity and Decoloniality: The Canadian Art Establishment’s New Clothes

- Cathy Lu’s ‘Interior Garden’ at the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco

- ‘In the Black Fantastic’: Afro-futurism Arrives at the Hayward Gallery

- On Caring Institutions, Safe Spaces and Collaborations beyond Exhibitions: An Interview with Robert Gabris

- Media Aesthetics of Collaborative Witnessing: Three Takes on ‘Three Doors – Forensic Architecture / Forensis, Initiative 19. Februar Hanau, Initiative in Gedenken an Oury Jalloh’ at Frankfurter Kunstverein

- Obituary: Marisa Rueda, 1941–2022

- The End Begins: A dialogue between Renan Porto and Julia Sauma, on the dialogue between Antonio Tarsis and Anderson Borba in ‘The End Begins at the Leaf’

- Sonia Boyce: Feeling Her Way at the Venice Biennale

- Clarissa Tossin: ‘Falling From Earth’

- The Collective Model: documenta fifteen

- Programmed Visions and Techno-Fossils: Heba Y Amin and Anthony Downey in conversation

- Reflections on Coleman Collins’s ‘Body Errata’ at Brief Histories, New York: Coleman Collins in conversation with Erik DeLuca

- Southern Atlas: Art Criticism in/out of Chile and Australia during the Pinochet Regime

- Jimmie Durham, ‘ “...very much like the Wild Irish”: Notes on a Process which has no end in sight’

- Jimmie Durham, ‘Those Dead Guys for a Hundred Years’

- The Many Faces of the Artist’s Studio – ‘A Century of the Artist’s Studio: 1920−2020’ at London’s Whitechapel Gallery

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Critical Zones – The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth’, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Wiebel

- Jimmie Durham, ‘A Certain Lack of Coherence’

- ‘Thought is Made in The Mouth’: Radical nonsense in pop, art, philosophy and art criticism

- Empowering Bare Lives: ‘Bordered Lives’ at the Austrian Association of Women Artists (VBKÖ), Vienna

- The Moral Stake of Gamification – On the ‘Black Swan: The Communes’ hackathon at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, August 2021

- ‘Departures’ at the Migration Museum, London

- BOOK REVIEW: David Elliott, ‘Art & Trousers: Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Asian Art’

- Jumping Out of the Trick Bag: Frank Bowling’s Lands of Many Waters at the Arnolfini

- Drawing From and With the Oceanic: Tania Kovats at Parafin, London

- BOOK REVIEW: Rachel Zolf, ‘No One’s Witness: A Monstrous Poetics’

- ‘Judy Baca: Memorias de Nuestra Tierra, a Retrospective’ at the Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California

- ‘Remembering in Art’: Kristina Chan in Conversation

- Living through Archives: The socio-historical memories, multimedia methodologies and collaborative practice of Rita Keegan

- Decolonising Dance Movement Therapy: A Healing Practice Stuck between Coloniality and Nationalism in Sri Lanka

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Feminism and Art in Postwar Italy: The Legacy of Carla Lonzi’, edited by Francesco Ventrella and Giovanna Zapperi

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Don’t Follow the Wind’, edited by Nikolaus Hirsch and Jason Waite

- Moyra Davey’s ‘Index Cards’ (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020) and ‘I Confess’ (Dancing Foxes, Press 2020)

- Why do we need Aby Warburg today? Or, is image memory a bodily sensation?

- BOOK REVIEW: Susan Schuppli, ‘Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence’

- Reflections on the Future and Past of Decolonisation: Africa and Latin America

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Under the Skin: Feminist Art and Art Histories from the Middle East and North Africa Today’

- Weaving and Resistance in Hana Miletić’s ‘Patterns of Thrift’

- BOOK REVIEW: Alana Hunt, ‘Cups of nun chai’

- BOOK REVIEW: The Avant-Garde Museum

- BOOK REVIEW: Dan Hicks, ‘The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution’

- Manora Field Notes & Beyond: A conversation with Naiza Khan

- Cara Despain, ‘From Dust’: Viewing the American West through a Cold War Lens

- ‘MONOCULTURE: A Recent History’ at M HKA

- Yishay Garbasz, in conversation with Sarah Messerschmidt

- ‘Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI’

- An Aesthetics of Prolepsis

- ‘Piercing Brightness’, by Shezad Dawood: Migration, Memory and Multiculturalism

- BOOK REVIEW: Deserting from the Culture Wars

- BOOK REVIEW: Saloni Mathur, ‘A Fragile Inheritance: Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian Art’

- At their word: Forensic Architecture’s renouncement and re-announcement of police testimonies in the investigation into the killing of Mark Duggan

- BOOK REVIEW: Sam Bardaouil, ‘Surrealism in Egypt: Modernism and the Art and Liberty Group’

- A conversation with Mohamed Melehi

- Heritage is to Art as the Medium is to the Message: The Responsibility to Palestinian Tatreez

- ‘We’, A Global Community Suspended in Time and Space: A Study of İnci Eviner’s Work in the 2019 Venice Biennial

- Grab the Form: A Conversation with Hafiz Rancajale

- ‘A Matter of Liberation: Artwork from Prison Renaissance’

- The Colonial Spectre of Classicism: Reflections on ‘White Psyche’ at The Whitworth Gallery

- BOOK REVIEW: Engagement or Acquiescence? On ‘Critique in Practice: Renzo Martens’ Episode III: Enjoy Poverty’

- ‘Errata’ in retro-prospect

- Cameron Rowland, ‘3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73’

- Pushing against the roof of the world: ruangrupa’s prospects for documenta fifteen

- BOOK REVIEW: Tom Holert, ‘Knowledge Beside Itself: Contemporary Art’s Epistemic Politics’

- BOOK REVIEW: Laleh Khalili, ‘Sinews of War and Trade: Shipping and Capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula’

- Maria Thereza Alves’s ‘Recipes for Survival’

- To Don Duration: Lisl Ponger’s ‘The Master Narrative und Don Durito in 10 Chapters’

- BOOK REVIEW: Oliver Marchart, ‘Conflictual Aesthetics’

- Karol Radziszewski's ‘The Power of Secrets’

- The Method of Abjection in Mati Diop’s ‘Atlantics’

- How are the visual arts responding to the COVID-19 crisis?

- Art in Contemporary Afghanistan

- BOOK REVIEW: Kate Morris, ‘Shifting Grounds: Landscape in Contemporary Native American Art’

- Boring, Everyday Life in War Zones: A conversation with Jonathan Watkins

- ‘Luchita Hurtado: I Live I Die I Will be Reborn’

- Movements, Borders, Repression, Art: An interview with artist Zeyno Pekünlü, March 2020

- ‘Shoplifting from Woolworths and Other Acts of Material Disobedience’, an exhibition of work by Paula Chambers

- Images in Spite of All: ZouZou Group's film installation ‘– door open –’

- Kamal Boullata: For the Love of Jerusalem

- Paul O'Kane, ‘The Carnival of Popularity Part II: Towards a “mask-ocracy”’

- BOOK REVIEW: Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, ‘Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism’

- ‘Knotworm’: Pauline de Souza interviews Sam Keogh

- BOOK REVIEW: Vessela Nozharova, ‘Introduction to Bulgarian Contemporary Art 1982–2015’

- A Place for/in Place of Identity? A conversation with Larissa Sansour

- Danh Vo’s Exorcism of Vietnam

- BOOK REVIEW: Jessica L Horton, ‘Art for an Undivided Earth: The American Indian Movement Generation’

- In conversation with Adam Pendleton: What is Black Dada?

- Edward Chell: ‘Common Ground’

- BOOK REVIEW: Jonas Staal, ‘Propaganda Art in the 21st Century’

- The 2019 Istanbul Biennial

- The Aliveness of Moses Quiquine

- ‘Terror Nullius’ by Soda_Jerk

- Archive Matters: Fiona Tan at the Ludwig Museum

- Communicating Difficult Pasts: A Latvian initiative explores artistic research on historical trauma

- BOOK REVIEW: Translating the World into Being - A review of ‘At Home in the World: The Art and Life of Gulammohammed Sheikh’

- Visiting the Arabian Peninsula: A Brief Glimpse of Contemporary and Not-So-Contemporary Art and Culture in KSA, aka the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- [AR]T, Apple and Us

- BOOK REVIEW: David Burrows and Simon O’Sullivan, ‘Fictioning: The Myth-Functions of Contemporary Art and Philosophy’

- Art and Theory in an Anti-fascist Year: An Interview with Kuba Szreder

- Paul O’Kane, ‘The Carnival of Popularity’

- BOOK REVIEW: Nora Sternfeld, ‘Das radikaldemokratische Museum’

- The 2019 Whitney Biennial

- ‘Passage to Asylum: The Journey of a Million Refugees’ – Dilpreet Bhullar in conversation with Kalyani Nedungadi and Maya Gupta

- On Brexit in Vienna: Mirroring the Social Decay

- Forever Young: Juvenilia, Amateurism, and the Popular Past (or ‘Transvaluing Values in the Age of the Archive’)

- Captain Cook Reimagined from the British Museum’s Point of View

- Okwui Enwezor: In Memoriam

- BOOK REVIEW: Chad Elias, ‘Posthumous Images: Contemporary Art and Memory Politics in Post-Civil War Lebanon’

- Arthur Jafa at the Berkeley Art Museum

- Repair, Ergonomics & Quantum Physics: Reflections on how Cairo’s contemporary art scene is reviving vanishing futures

- Vivan Sundaram: Disjunctures

- Rome Leads to All Roads: Power, Affection and Modernity in Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Roma’

- Still Caught in the Acts: ‘Mating Birds Vol. 2’

- A Political Gemstone Kingdom of Natural–Cultural Feelings from Bucharest to Warsaw: Larisa Crunțeanu’s ‘Aria Mineralia’ exhibition

- INTERVIEW: The Politics of Shame – Ai Weiwei in conversation with Anthony Downey

- BOOK REVIEW: Renate Dohmen’s ‘Encounters Beyond the Gallery’

- Juliet Steyn reviews Juan Cruz’s ‘I don’t know what I’m doing but I’m trying very hard.’

- INTERVIEW: Mediating Social Media – Akram Zaatari in Conversation with Anthony Downey

- An Indigenous Intervention: Richard Bell’s Salon des Refusés at the 2019 Venice Biennale

- INTERVIEW: Sunil Shah, ‘Uganda Stories’

- Zarina’s ‘Dark Roads’: Exile, Statelessness and the Tenacity of Nostalgia

- BOOK REVIEW: ‘Fahrelnissa Zeid: Painter of Inner Worlds’ by Adila Laïdi-Hanieh

- BOOK REVIEW: Iain Chambers, ‘Postcolonial Interruptions, Unauthorised Modernities’

- The 2017 Venice Biennale and the Colonial Other

- BOOK REVIEW: David Kunzle, ‘CHESUCRISTO: The Fusion in Image and Word of Che Guevara and Jesus Christ’

- Longing for Heterotopia: ‘Silver Sehnsucht’ in Silvertown

- BOOK REVIEW: Future Imperfect: Contemporary Art Practices and Cultural Institutions in the Middle East

- Art as Anachronism

- INTERVIEW: John Akomfrah

- Steven Eastwood: ‘the interval and the instant’

- BOOK REVIEW: Open Systems Reader - Tomorrow is not Promised! edited by Gulsen Bal

- Paul O’Kane, ‘The Other Side of the Word: Translation as Migration in the Anthologised Writings of Lee Yil’

- ‘The Self-Evolving City’: Architecture and Urbanisation in Seoul

- The Folkestone Triennial 2017

- Sharjah Biennial 13 Offsite: Ramallah

- Theory of the Unfinished Building: On the Politico-Aesthetics of Construction in China

- Marcus Verhagen, ‘Flows and Counterflows: Globalisation in Contemporary Art’

- An Architecture of Memory

- Learning from documenta 14: Athens, Post-Democracy, and Decolonisation

- BOOK REVIEW: Joan Key, ‘Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method’

- Kader Attia: Dispossession

- BOOK REVIEW: Zhuang Wubin, ‘Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey’

- Spectral Anxieties of Postculture

- 'Exercises of Freedom': Documenta 14

- Bloom

- Artes Mundi 7

- Post-Perspectival Art and Politics in Post-Brexit Britain: (Towards a Holistic Relativism)

- A Short History of Blasphemy

- BOOK REVIEW: Moulim El Aroussi, ‘Visual Arts in the Kingdom of Morocco’

- The Vicissitudes of Conduct

- South Korea’s Painful Past

- Return of the Condor Heroes and Other Narratives

- ‘The Savage Hits Back’ Revisited: Art and Global Contemporaneity in the Colonial Encounter

- The Unrepresentables

- From a Postconceptual to an Aporetic Conception of the Contemporary

- Christof Mascher: Memory Palace

- The 6th Marrakech Biennale, 2016: ‘Not New Now’

- The 2015 Venice Biennale

- Art in the Time of Colony

- Brad Prager, After the Fact: The Holocaust in Twenty-First Century Documentary Film

- In Media Res: Heiner Goebbels, Aesthetics of Absence: Text on Theatre

- Failure as Art and Art History as Failure

- Restrictions Apply

- 13th Istanbul Biennial

- ‘Re: turn’: Bashir Makhoul

- Global Occupations of Art

- The Politics of Identity for Korean Women Artists Living in Britain

- Art Beyond Conflict

- David Craven’s Future Perfect

- Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology

South Korea’s Painful Past

"Like Documenta, the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea was also initially prompted by a tragic historic event. The massive quinquennial Kassel exhibition is the world’s most important art event and evolved in reaction to the WWII bombings that destroyed almost the entire city centre. The Gwangju Biennale was founded in 1995, commemorating the student uprising that began on 18 May 1980, when the government deployed tanks and paratroopers to violently beat down on protests against the dictator Chun Doo-hwan. More than 200 civilians were killed, many more were injured, imprisoned or vanished. Numbers differ, depending on the historical source."

Christian Chambert

Unidentified skulls and other skeleton parts from Gyeongsan and Jinju are faintly visible through the windows of artist Minouk Lim’s two cargo containers in front of the Biennale building in Gwangju. They are part of her new performance work Navigation ID (2014), relating to Korea’s conflict-ridden twentieth-century history.

After Japan’s occupation (1910–1945), the country was racked by conflicts between the superpowers. In the ensuing Korean War, some 200,000 civilians were executed on orders from the South Korean government, for alleged communism or North Korean sympathies. At the time, US troops near No Gun Ri killed at least 300 civilian refugees. Not until Associated Press brought this to world attention in 1999, was the massacre discussed in the South Korean media.

Like Documenta, the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea was also initially prompted by a tragic historic event. The massive quinquennial Kassel exhibition is the world’s most important art event and evolved in reaction to the WWII bombings that destroyed almost the entire city centre. The Gwangju Biennale was founded in 1995, commemorating the student uprising that began on 18 May 1980, when the government deployed tanks and paratroopers to violently beat down on protests against the dictator Chun Doo-hwan. More than 200 civilians were killed, many more were injured, imprisoned or vanished. Numbers differ, depending on the historical source.

Minouk Lim’s performance reminds visitors of the events of 18 May 1980. It also individualises the civilians who were executed during the Korea war in the early 1950s, albeit namelessly, freeing them temporarily from the rival ideologies that brutally separated the North and South Korean populations. The containers are randomly placed off-piste on the plaza, accentuating this depersonalisation. In the midst of the bustling city, these containers get closer to the non-gallery-going public. The work challenges South Korean neoliberal political rhetoric which stresses economic and material progress. Instead of processing the events, the elected representatives have hushed-up the assaults against citizens in the 1950s and 1980s.

These bone-filled vessels allude to the commodities shipped across the oceans of the world. Containers adapted to the requirements of international shipping have rapidly contributed to the globalisation of trade. Here, they are a reminder both of the affluent society’s poor waste disposal, and of the crews on starvation wages on-board ships registered under flags of convenience.

Jeremy Deller, Untitled, 2014, print on flex canvas; Minouk Lim, Navigation ID, 2014. Gwangju Biennale's plaza. View of containers from Jinju and Gyeongsan with remains of civilian massacre's victims during the Korean War 1950.

Minouk Lim, Navigation ID, 2014. View from inside of Jinju container's shelves, the remains of Jinju civilian massacre's victims during the Korean War 1950. Excavation date: 2014.2.24~3.2. Courtesy of Minouk Lim. Photo by Minouk Lim.

NEW SOUTHERN AND EASTERN BIENNIALS ATTRACTING ATTENTION

Some thirty artists at the Gwangju Biennale are South Korean. Two of them, the women artists Minouk Lim and the internationally-established Lee Bul, are extensively featured as figureheads of the exhibition. The internet publication Artnet News ranks Gwangju fifth among international ennials, ie regularly recurring large-scale exhibitions. Outside Europe and the USA, they are number one. The latest Gwangju Biennale ingeniously highlights Asian and non-Western art, while discussing South Korea’s history. The 2014 Biennale had some 200,000 visitors in sixty-six days – a daily average exceeding 3,000. The Venice Biennale in 2013 had more visitors in total and lasted for nearly six months, but had lower daily visitor numbers. This gives some indication of the Gwangju Biennale’s status and attraction, despite not having the same interest for international mass tourism.

TIGER ECONOMY

An analysis of the latest Biennale in Gwangju requires a short background on the drastic social changes in South Korea since the early 1980s. In only a couple of generations, South Korea has transitioned from a poor agrarian society into one of Asia’s richest and most densely populated nations. Travelling through the mountainous landscape, I see clumps of white high-rise buildings that remind me of inexpertly inserted dental implants. Shooting out of the earth like fast-growing bamboo after a rainfall, their floor levels resemble nodes on the plant stems. Samsung’s spectacular art museum Leeum, in Seoul was designed by the European architects Mario Botta, Rem Koolhaas and Jean Nouvel. To be on the safe side, the mighty South Korean company employed three internationally renowned masters. Leeum’s facade presents the nocturnal wanderer with a bright neon legend: memories of the future. The title of French artist Laurent Grasso’s work proclaims: forget the nation’s destructive past but remember its leap towards a brilliant future. The Gwangju Biennale also aims for the stars now that the old social structure has been razed. Many of the artists at the Biennale do backward somersaults to erstwhile politically charged events in South Korean history, specifically in Gwangju, exploring them from their foothold in contemporary radical culture.

Laurent Grasso, memories of the future, 2010, Leeum, Seoul. Photo © Christian Chambert.

Jessica Morgan, from the UK, is the first woman to have primary responsibility for the Biennale. Previously, top curators Okwui Enwezor and Massimiliano Gioni have contributed to the event’s international recognition. With the exhibition title, ‘Burning Down the House’, Jessica Morgan asserts a tabula rasa philosophy, where old structures are wiped out in favour of viable initiatives. Diligently, she has amassed works that somehow relate to houses or fires, not always contributing to the overall meaningfulness of the exhibition.

The Biennale has borrowed its title from a Talking Heads track from 1983, which embodies the ambition of the new wave to combine lyrical complexity with social commitment, which, unfortunately, ends in a mantra about setting fire to a building. A more pertinent wakeup call would have been a reference to Marquis de Sade’s Les 120 journées de Sodom (The 120 Days of Sodom) from 1785, where Judge Curval, in an oft-quoted passage, wants to destroy the sun or use it to set the world ablaze.

THE ARDUOUS STRUGGLE FOR DEMOCRACY

South Korean Hwang Sok-yong’s long novel Oraedoen chǒngwǒn (The Old Garden, 2000) is an excellent starting point for learning about Korea’s modern history and gaining a deeper understanding of the Biennale’s theme. The main protagonist O Hyǒnu is arrested for participating in the 1980 rebellion in Gwangju and Seoul. On his release after eighteen long years in prison, he returns to his former hideout, where the farming village has been replaced by high-rise buildings, and the love of his youth, Yunhŭi, is dead. The idealists eventually get the change they fought so hard for, but new problems loom. The book points out the minimal role of enthusiasts in the fight between autocracy and extreme market liberalism.

Huma Mulji, Lost and Found, 2012, fibreglass and buffalo hide. Photo Credit: Stefan Altenburger.

CENSORSHIP AND BOYCOTT

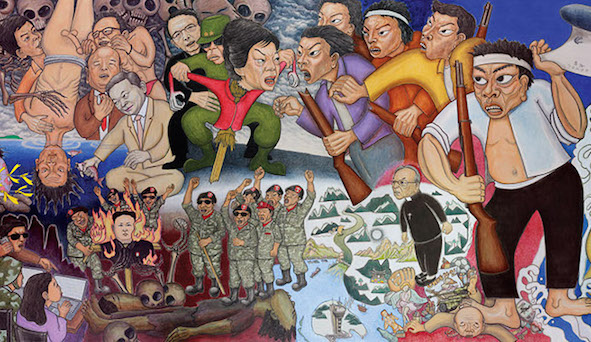

A commemorative exhibition held in conjunction with the Biennale (‘Sweet Dew – After 1980’) at the Gwangju Museum of Art, was subjected to severe censorship and duly boycotted by several artists. When news of the decision to withdraw Hong Sung-dam’s painting broke, numerous artists withdrew from the show, several others pointedly obscured their work with anti-censorship messages, a key loan was cancelled and the respected president of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation, Lee Yong-woo, resigned. When the piece was first revealed to GMA officials, just hours before the 8 August opening, according to the biennale foundation, the museum called a meeting with foundation leaders to discuss whether the painting should be included. At this meeting it was decided that the question should be deferred to a public forum on 16 September. The artist then withdrew the painting. There is no information as to exactly when the painting was withdrawn. The controversy concerned Hong Sung-dam’s more than ten-metre long painting Sewol Owol. South Korea’s woman president, Park Geun-hye, is identified as being responsible for the major ferry disaster off the South Korean coast in spring 2014 which claimed the lives of 250 students. In the censored painting, Park morphs into a furious scarecrow held tight by her father, the dictator Park Chung-hee, whose regime provoked the student rebellion in Gwangju in May 1980. The artist short-circuits the 1980 rebellion with the sinking ferry disaster, in both cases ruthlessly criticising the same long-lived presidential family. Apparently, more presidential palaces should be burned to the ground, at least symbolically.

Hong Sung-dam, Sewol Owol, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 290 x 1260 cm, © and photo © the artist.

Detail from Hong Sung-dam, Sewol Owol, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 290 x 1260 cm, © and photo © the artist.

A CRITIQUE OF SOCIAL AND POLITICAL OPPRESSION

One way of effectively making people feel shame and lowering their self-esteem is to compare them to animals. Pakistani artist Huma Mulji’s fibreglass work Lost and Found (2012) blends the human and animal genomes. A humanoid form is covered in buffalo hide turning it into a hirsute beast. The work challenges normality and our fear of becoming monsters that can take control over our lives. The bestial creature is uncanny not for being bestial but for partaking of human form. The Pakistani secret service are searching for alleged terrorists, the suspects are tortured and murdered; this dehumanisation, literally ‘making animal’, could be seen as the authorities justification for their actions. A twist in this sinister masquerade is that the buffalo is part of traditional, safe rural life in Pakistan. Against this stands the abandoned, anonymous, water-bloated man thrown into the canal from the back of a lorry.

Renata Lucas, until it becomes an inconvenient stranger, 2014, architectural intervention. © Stefan Altenburger Photography.

ART AND CRITIQUE IN THE MAZE

Brazilian Renata Lucas captures the social situation in South Korea by quoting the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy: until it becomes an inconvenient stranger. She inserted an oblong window in the Biennale building’s south blind wall, mirroring the windows of the architecture facing it. The installation refers to apparently endless rows of similar windows in standardised houses scattered across South Korea. Lacking aesthetic features or attention to detail, the high-rise structures are reduced to mere dwellings. Only the large number plaques and the property owners’ logotypes high up on the facades distinguish them from one another. Lucas work highlights the enormous need for housing in the wake of rapid population growth, while levelling a subtly poignant warning against conformity, alienation and high-rise developments. Carsten Höller’s seven electronic, mirrored sliding doors at the exit open one by one as I approach, only to shut behind me. The organiser stresses that the way forward is what counts. A Biennale host stops visitors from retracing their steps through the exhibition about the burned-down house, a parallel to Lot and his family escaping while Sodom and Gomorrah go up in flames. Disobeying God’s command, Lot’s wife turned back towards the past, the burning cities, and was transformed into a pillar of salt.

Carsten Höller, Seven Sliding Doors, 2014, steel, glass, mirror foil, electric motors, door mechanism, wiring, fabric, lighting, movement detectors, length 25,2 m (distance between two doors 4,2 m), height 2,4 m.

The 10th Gwangju Biennale: ‘Burning Down the House’, ran from 5 September to 9 November 2014 in Gwangju, South Korea. Burning Down the House: Gwangju Biennale 2014, exhibition catalogue, 2014, Damiani srl, Bologna. www.damianieditore.com, was published after the end of the Biennale.

Christian Chambert is an art critic and art historian living in Uppsala. He was President of AICA Sweden 1978–2013 and organized the AICA Congress in Stockholm and Malmoe in 1994. Together with Katy Deepwell, Kim Levin and John Peter Nilsson he was the editor of Art Planet (1999) and was the editor of Strategies for Survival – Now! (1995). He has written for Colóquio Artes, Hjärnstorm, Neue Bildende Kunst, Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, NU: The Nordic Art Review, Paletten, SIKSI and Taide, among others. He chaired AICA’s Website Commission (2012–2015) and is chairing AICA’s Sub Commission on Statutes and Regulations (2013–).

Translated from Swedish by Gabriella Berggren