Third Text

- Thinking Gaza: Critical Interventions

- Living Archives

- Decolonial Imaginaire

- Decolonising Colour?

- ‘Artist and Empire’ Part 2: Singapore (2016–2017)

- ‘Artist and Empire’ Part 1: Tate Britain, London (2015–2016)

- Emilia Terracciano, ‘Dispelling the Myth of the “Positive Legacies” of Empire’

- Renate Dohmen, ‘All Bark and No Bite: India at Tate Britain’s “Artist and Empire” Exhibition’

- Natasha Eaton, ‘Tired Ornamentalism’

- Nicola Gray, ‘Echoes of Empire: “Artist and Empire” at Tate Britain’

- Louis Allday, ‘On (Not) Facing Britain’s Imperial Past at Tate Britain’

- Jessyca Hutchens, ‘Ambiguous Narratives: “Artist and Empire” at Tate Britain’

Echoes of Empire: ‘Artist and Empire’ at Tate Britain

Nicola Gray

For an institution whose very existence originates in Britain’s imperial history to mount an exhibition of the visual legacy in the images and artefacts that were produced in relation to and because of that history is probably bound to result in a flawed project. Tate Gallery’s origins are clear in its name. Henry Tate began his working life in grocery shops in Liverpool, then made his fortune in sugar refining (and through purchasing the patent for sugar cubes from its German originator); and sugar, of course, was one of the main commodities behind the brutality of the slave trade. His name also lives on in the Tate & Lyle multinational agribusiness. Henry Tate amassed a collection of British art that he wanted to bequeath to the nation, but with an already full National Gallery the decision was made to build a separate museum dedicated to British art. Tate funded the building himself, anonymously initially, and it was not actually named the Tate Gallery until 1932. Another of these echoes of empire which reverberate through so many of London’s institutions, streets and monuments is that the location chosen for what would become the future Tate Britain was originally the site of the Millbank penitentiary, from which convicts would have been led onto ships to Australia – just one of the multiple narratives and histories of the far reaching tentacles of the British Empire.

‘Artist and Empire’ is an odd title. It carefully avoids the question of which artists, what kind and from where, and presents us with the generic ‘artist’; maybe as a nod to the equalising and levelling framework the exhibition attempts. ‘Art and Empire’ would not have been very accurate either. But if I have cavils about the use of ‘artist’ and ‘art’, what is beyond question is that the exhibition is most definitely framed through a still imperial lens, and it is a view from deep inside the centralised core of its original heart.

The British Empire was the largest, most far reaching empire the world has yet seen, and relatively rapidly acquired. Although much of what became the Empire had, at different times, been the setting for various ‘encounters’ with other European colonial ambitions (mainly France, Holland, Spain and Portugal), by the nineteenth century it was Britain that had triumphed. After World War I and the defeat of Germany and its allies (principally Turkey, thus bringing about the end of 650 years of the Ottoman empire), the small island kingdom off the northwest coast of Europe found itself governing, either directly or indirectly, about 500 million people—more than one fifth of the planet’s population. Britain’s early (although not the first) colony, the subsequent United States of America, is not included in this calculation as it broke away into independence in 1776. The first colonial enterprise, Ireland, remains an ongoing issue.

The Empire was closely intertwined with the rise of commerce and trade, and hence the entrenchment of capitalism. It profoundly shaped the modern world, and its legacies have had lasting and major consequences that continue to reverberate in many corners of the globe. To show the visual images and cultural artefacts produced in the numerous levels and arenas of this enterprise, and to examine the relationships and events they arise from and portray, is a colossal and daunting task, one that is fraught with problematic decisions and viewpoints to be negotiated (or it should be). The exhibition, not surprisingly, falls short. I hesitate to categorically state that it fails completely, but the result is a distinctly ‘soft’ view. Despite some of its declared aims, it is almost a celebration of empire, glossing over and obscuring the damage, destruction and profound changes that British imperialism wreaked on ‘other’ cultures and lives.

The exhibition begins with ‘Mapping and Marking’, the essential tools for naming and claiming territories and demarcating boundaries. This is the most clearly realised of the seven thematic sections; and perhaps the least problematic. The Empire was inscribed/described on vellum and paper in order to visualise the topography and thence the clarification of claims to the land. Maps can elucidate more than their superficial depictions, however. Matthew Flinders’ General Chart of Terra Australis… showing the parts explored between 1798 and 1803 (1814), for example, gives a clear outline of ‘New Holland’, or ‘Australia’ or ‘Terra Australis’, but contains no information on the interior. Flinders was in the Royal Navy and his brief had been to explore the previously ‘unknown’ southern coast. He mapped the continent – except for its west coast, which he was unable to approach closely enough because of difficult terrain and rough seas presumably – and when reproduced as an engraving his map contributed to the familiarity of the iconic image of the continent’s shape and is partly responsible for the general adoption of the name ‘Australia’. Other maps and topographical drawings show the gradual establishment of the empire and the expansion inland from ports and forts, from Diogo Homem’s attempt to map the world in The Queen Mary Atlas (1541), through Wenceslaus Hollar’s The Settlement at Whitby (1669), to other mappings of New York, ‘Bombay’ and ‘Calcutta’.1 The nineteenth- and early twentieth-century world maps, such as Walter Crane’s Imperial Federation map from 1886, with their spread of pink-coloured territories, illustrate the extent and size that the imperial dominions came to be in a relatively short space of time. Maps produced only a few years later than Crane’s would have even more pink. With the ‘British Isles’ positioned at the central focal point of the distorted Mercator projection view of the world, such maps portrayed a Britannia that truly ruled the waves. Crane was a Victorian socialist and member of both the Fabian Society and William Morris’s Social Democratic Federation and produced his map for the Imperial Federation League, an organisation that proposed a single federated state of all the colonies as an alternative to the colonial model. (A seed for what later became the Commonwealth, perhaps?) The choice of this particular map, with its storybook depictions around the edge of the Empire’s ‘characters’, and not other later, and pinker, ones (which surely exist), suggests the distinctly liberal perspective on empire that the exhibition represents.

Walter Crane (1845–1915), Imperial Federation Map, 1886. Colour lithograph. 600 x 785 mm. Daniel Crouch Rare Books.

All the exhibits have been drawn from museums and collections in the UK. Nothing has been borrowed from collections or museums elsewhere. A glance at the lenders shows contemporary institutions that were intricate parts of and companions to British colonialism: the British Museum, the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, the Natural History Museum, the Royal Botanic Gardens, the National Maritime Museum, and the National Army Museum, among others.2 This may have been a budgetary decision, a practical one to reduce the scope of an ambitious undertaking. According to curator Alison Smith’s catalogue introduction, however, it was a conscious choice to only consider the visual stuff of Empire that was available to be seen at its heart, a perspective bound inevitably to produce a limited vision. Yet the impression is given that much of this stuff is no longer in the mainstream, that the image-history of empire has been hidden away and forgotten. This is undoubtedly true, especially with some of the portraits and the paintings of battle scenes. Elizabeth Butler’s The Remnants of an Army: Jellalabad, January 13th, 1842 (1879), for example, with its sunset image of a lone battle-weary survivor, was in Henry Tate’s original collection, but has been on long term loan to the Somerset Military Museum Trust since after World War II. In the second half of the twentieth century, following the modernist movement and the War, when museums were emptied and collections hidden in secret locations in case of a German invasion, many works were simply never taken out of storage or went on permanent loan elsewhere. An institution such as the Tate was shifting its focus to the ‘modern’ and across the Atlantic to the US, and heroic images of battles and dated portraits of colonial dignitaries didn’t fit with the trajectories of modernism.

Many of the institutions and collections where the ‘Artist and Empire’ exhibits have been sourced must have vast collections of artefacts related to Britain’s imperial history. The National History Museum’s finely detailed illustrations of insects, animals and plants from far-flung lands are directly related to colonisation and journeys of exploration. The British Museum has many hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of items in its storerooms that are intimately connected to empire as a direct result of the British presence in so many parts of the world. But such theft – it can really only be called that – and on such a scale, is not a significant part of the picture portrayed in ‘Artist and Empire’.

Instead, the exhibition strives to find a more positively nuanced perspective; to show a picture of collaboration, mutual learning and cultural mixing. It even claims to be part of the process of breaking down a perceived silence on the legacies of empire, and of a reassessment of British identity following the independence referendum in Scotland and the debate over Britain’s membership of the European Union. The portraits of captains, lieutenants and colonial governors wearing Indian silks or eagle feather headdresses are presented almost as if they illustrate some fun cross-cultural dressing-up. But in marked contrast to the confident looks in the portraits of those in positions of colonial power is the profound sadness clearly visible in some of the photographs in the eyes of those subjected to that power. Also hinting at other stories are Gilbert Stuart’s 1786 portrait of the Mohawk Thayendanegea (aka Joseph Brant), who collaborated with the British army in the confederate wars and spent time in London society circles, and Simon de Passe’s 1616 engraving of Pocahontas (aka Rebecca Rolfe), who is thought to lie buried under a church in Gravesend in Kent. The decimation of Native American peoples and cultures throughout North America through disease, land grabs and war, that is a direct legacy of mainly British settlement, continues to have profound impacts to this moment.

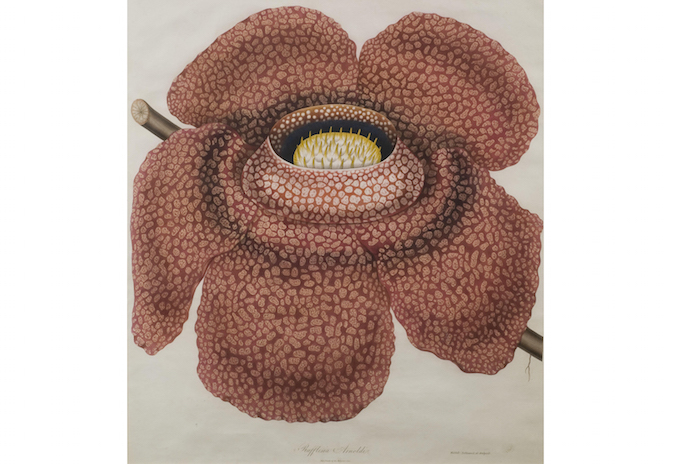

There was undeniably some cross-fertilisation, to use a botanical metaphor. But it was never on equal terms, and this is a crucial point that ‘Artist and Empire’ fundamentally fails to communicate in its exhibition format, although some of the catalogue texts do expound more on this. The exhibition includes botanical drawings by Indian and Chinese artists, for example, which are executed in a style that is a blend of their traditional techniques and European influences. Shaik Zain-ud-Din, the artist from Patna who produced the wonderful Common Crane (1780), is named, although the ‘Chinese artist’, or artists, who executed the undated gouaches of Two Fish and the two plumaged birds Tragopan Temminckii (Temminck’s Tragopan) is not. Both would have been hired or commissioned. Sir William Jones, on the other hand, a judge at the Supreme Court in ‘Calcutta’, and his wife, Anna Maria, were enthusiastic amateur botanists and made conscious efforts to learn the Sanskrit or Bengali names for indigenous plants, as well as the Linnean classifications. Naming is a colonial practice in its own right, and European names crept into these Linnean terms as ‘new’ plants were ‘discovered’, documented and classified. Sir Stamford Raffles, for example, the Governor of British Java and the ‘founder’ of Singapore, not only left his legacy in the city’s famous Raffles Hotel, but also in Rafflesia Arnoldii, the one-metre sized parasitic ‘corpse flower’ native to southeast Asian forests, allegedly ‘discovered’ by Raffles and a naval surgeon, Joseph Arnold, on an 1819 expedition, although actually pointed out to them by a Malay guide.

E. Weddell (fl 1800–1825), Rafflesia Arnoldii, 1826. Hand-coloured engraving on paper. 950 x 750 mm. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, London.

The imperial practices of naming are worthy of further study in their own right and are so taken for granted in the modern world as to often go unnoticed. To write ‘Calcutta’ or ‘Bombay’, not Kolkata and Mumbai, and to continue using the colonial way of writing the names (which the exhibition does), is a measure of how embedded the Empire’s legacy is. The Empire, and those who surveyed, governed and travelled it, lives on in its namings. Virginia, Georgia, New York, Queensland, New South Wales, the Cook Islands, Londonderry, Victoria Falls, Port Elizabeth, Charleston, the Possession Islands, Wellington, are only a few examples, but there will be many more thousands of streets, public squares and coastal bays whose names carry within them histories of conquest and control.

The final three sections of the exhibition (‘Face to Face’, ‘Out of Empire’ and ‘Legacies of Empire’) lack some clarity and historical and intellectual rigour. The catalogue essays are more enlightening, although I disagree with Carol Jacobi when she categorises the encounters between the embodied representatives of the Empire and the colonised subjects as ‘trans-national exchanges’, as she does in her catalogue essay ‘Face to Face’. Such terms sanitise complex power relationships and imply a fanciful relational equality. Jacobi does admit that ‘the vast majority of [the people touched by empire]… were never reflected’ in any form of visual representation, and also says that the scarce ‘non-British oral, written and visual records… were lost when the cultures that made them changed, or were usurped, dispersed or destroyed’.3 These are the not-visible sources absent from the exhibition. But, nevertheless, on a closer look, there are subtle evidences in ‘Artist and Empire’ of this other side of the story.

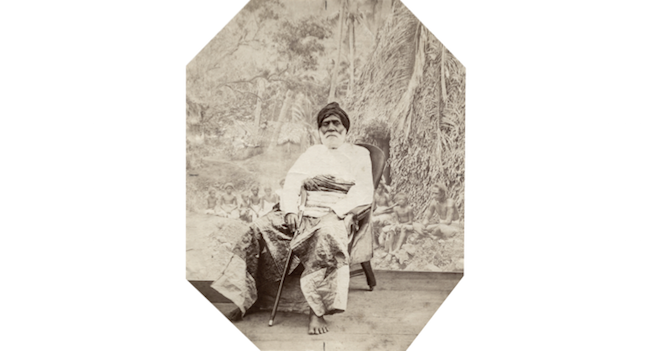

With the exhibition’s broad-brush approach to a weighty history, and a deeply centralised perspective that only partially looks outwards and makes no attempt to look back at itself, it was the not-so-obvious details in the backgrounds and corners that gave a glimpse of the other stories. The ghosts in the imperial machine maybe; the echoes of empire that continue to make sound. The tiny line of manacled slaves (called ‘prisoners’ in the catalogue text) in the lower right corner of Nicholas Pocock’s A View of the Jason Privateer (1760). Ikmallik and Apelagliu, the two Inuit men on board the ice-trapped paddlesteamer Victory that had been searching for the northwest passage around North America, drawing a map to show their local knowledge in James Brandard’s 1835 lithograph.4 The line of ‘natives’ in the photographic backdrop that was later added to the Dufty brothers’ studio portrait (1873–1876) of the Fijian leader Ratu Seru Cakobau. The scattered corpses from the Opium Wars’ Third Battle of Taku Forts in Felice Beato’s 1860 photograph from his album ‘The Views of China’ (in his carefully set up photographs, Beato only ever depicted the enemy’s dead).

Alfred W. Dufty and Francis Herbert Dufty, Ratu Seru Cakobau 1873–6, Albumen print, 30 x 20 cm. This image is copyright. Reproduced by permission of University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (P.99836.VH).

The concluding two sections, ‘Out of Empire’ and ‘Legacies of Empire’, bring us into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, featuring works by artists who moved to London in the post-war, post-independence years, and by artists from a younger generation, born in the UK whose parents came from the former colonies, and who studied and forged their careers within the British system. Considering that there are ample sources that could have been engaged with for a more rigorous analysis of the histories of artistic practice in the postcolonial era, the works are selected for their playful, but also critical, links to the rest of the exhibition. The terms ‘trans-national modern art’ and ‘national modern art movements [that] evolved on a world stage’, as used by Carol Jacobi in her catalogue essay ‘Out of Empire’, imply a level playing field and implicitly shared ideologies, amongst the earlier generation of artists particularly, whatever their geographical and cultural origins.5 But this suggests a false picture of similarly shared successes and parallel careers. The artists who came to the ‘centre’ from the former colonies did have some initial success in the 1950s and 1960s, but as the institutions, and the market, shifted their focus to the US, and as New York became the ‘centre of the artworld’ in the latter half of the twentieth century, these artists had a difficult and problematic relationship with Britain’s gatekeeping and career-supporting institutions. Ronald Moody, Aubrey Williams, Donald Locke and Avinash Chandra, for example, were key figures in this move. The artist, writer and publisher, Rasheed Araeen, who came to London from Pakistan in 1964, is noticeably absent from the exhibition, and considering the Tate has thirteen of Araeen’s works in its collection, it is striking that his work is not included in ‘Artist and Empire’. His contribution as a writer and publisher to the debates concerning the relationship of artists from the former colonies to the institutionalised parochialism they frequently encountered in the former empire’s heart is not mentioned, and neither is he given due credit as the initiator and curator of the seminal 1989 exhibition ‘The Other Story’ at London’s Hayward Gallery (although this is mentioned briefly in the catalogue). ‘The Other Story’ (which took eleven years to realise) sought to give visibility to artists who had come from postcolonial societies and cultures and their engagement with modernism but who found the British establishment’s doors did not readily open to admit them.6

Rita Donagh (b. 1939), Shadow of Six Counties, 1980. Graphite and acrylic on paper. 360 x 362 mm. Tate Collection.

Perhaps it is in the work of two of the more contemporary artists, Rita Donagh and Judy Watson, where we can see some of the more critically relevant and current negotiations artists are making with the heritage of Empire – Donagh, with her subtle imagings of the colonial legacies in Northern Ireland, and Australian-Aboriginal artist Judy Watson in her three etchings, our hair in your collections, our bones in your collections and our skin in your collections (1995), whose titles need no further explanation. ‘Artist and Empire’ was a missed opportunity to investigate the cultural production and legacy of a force that has had a profound impact on millions of lives, and on geographies and topographies, languages and cultural practices. Instead of what it could have been, it was a fairly anaemic, superficial and romantic view from the empire’s heart, with occasional glimpses of the other side of the story to be told by millions of silent, or silenced, voices. The detailed information and some of the texts in the catalogue make up for some of that silence, but voices continue to exist that have still not had any channels opened up for them to display their own versions of their histories’ visual legacies.

1 ‘Whitby’ was a British settlement built at Tangier when it was ‘given’ to England in 1661 as part of Charles II’s marriage contract with the Portuguese Catherine of Braganza. The settlement was abandoned after little more than a decade.

2 The apparent absence of any artifact from more recent institutions, such as Liverpool’s International Slavery Museum, for example, is telling.

3 Carol Jacobi, ‘Face to Face’, Artist and Empire, Tate Publishing, 2015, p 151

4 The small lithograph, based on a drawing by the explorer John Ross, was included in Ross’s book Narrative of a second voyage in search of a north-west passage, and of a residence in the Arctic regions during the years 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833, London, AW Webster, 1835.

5 Artist and Empire, op cit, p 207

6 See Jean Fisher’s excellent paper in the Tate’s own online Tate Papers: Jean Fisher, ‘The Other Story and the Past Imperfect’, in Tate Papers, no 12, Autumn 2009

Nicola Gray is a freelance artist, writer and editor normally based in the UK. She has been collaborating with Palestinian artists and cultural organisations since 2002 on residencies, exhibitions, writing and publication projects.